In the old days, most everyone in Muleshoe and Bailey County probably knew about Josh Blocher and his quest to make Progress the most successful town in Bailey County. They also had heard tales of the money he was said to hoard and bury around his house, tales others had heard as well, which ultimately led to his sad and unnecessary death. Pat Watson’s dad, C.C. Morgan, was a Baptist preacher for a time in Progress and visited with Josh frequently. Pat had a soft spot for Josh as years past and he became more reclusive and eccentric, and she thought his was a story that ought to be told. Most of the old-timers who could have filled in the blanks of this strange story have long been gone, but some of the children of those families are still around and did their best to share the details they could remember. Pat shared copies of news articles about the murder. Corky Green provided a bound copy of the trial transcript. The Tales and Trails of Bailey County history book came in handy as well. This is the story of an odd, lonely old man who chased dreams of grandeur for the city of Progress, but who ended up living a life filled with mystery and poverty.

Around 1907 or 1908, Joshua Blocher (spelled with an ‘h’ but pronounced as a ‘k’) came to Bailey County from Kansas, perhaps from some town in Willow Springs Township, Douglas County, as that was listed as his birthplace. He told people he had been a hypnotist; others said he was a magician in a traveling tent show. Neither occupation sounds like a high-paying profession to me, but he came to Bailey County with enough money to become a land speculator of sorts.

An article in the Bailey County history book makes reference to people moving to this area of Texas about this time with the promise of cheap land and good water. Josh might have heard these reports and saw an opportunity make some money and a name for himself. In 1920 the population of Muleshoe was 517; in a mere ten years that number had jumped to 5,186 by 1930. Perhaps Josh was just ahead of the curve, anticipating the area developing as people moved here. So why not be the one to start a town and sell residents their land?

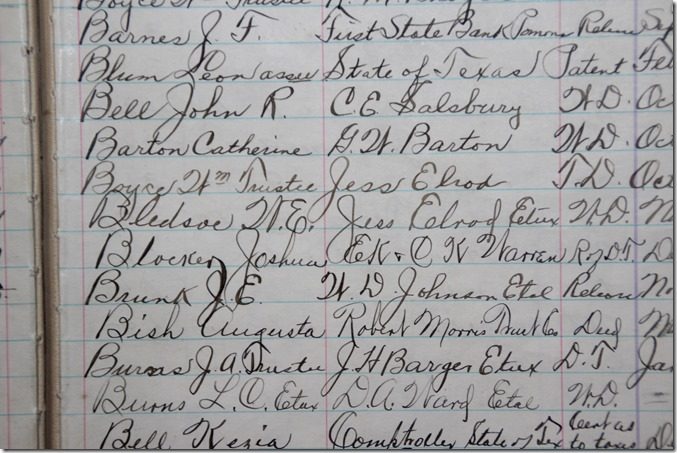

The Index of Deeds in the courthouse shows that he bought and sold land several times before his purchase in 1919 of the land that was to become Progress.

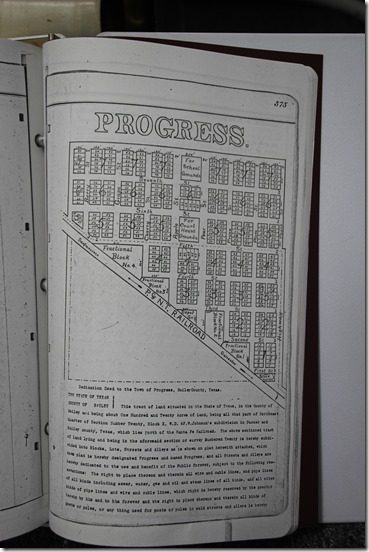

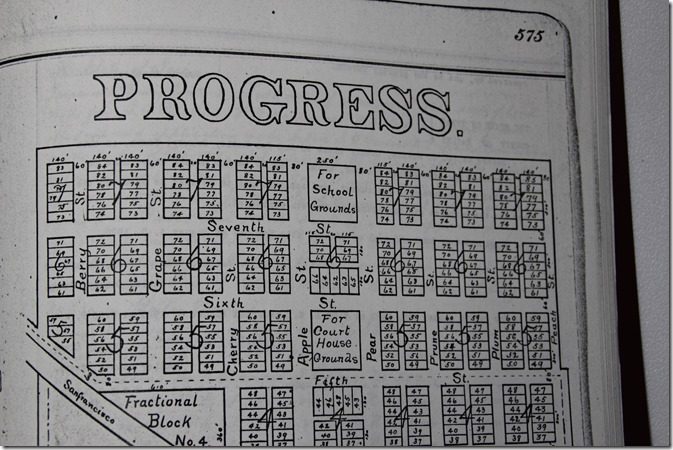

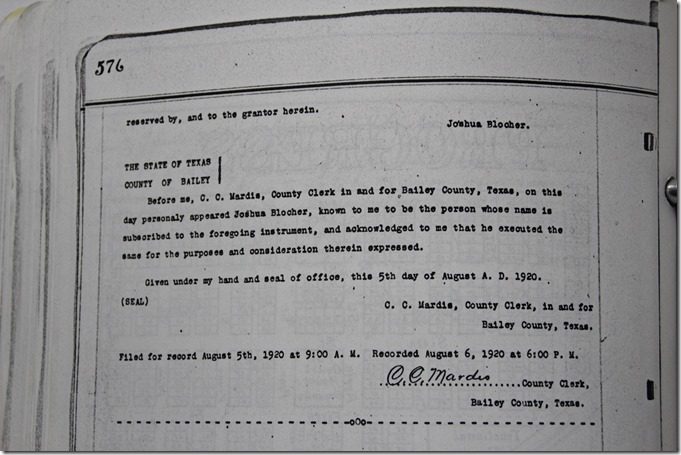

Josh bought Block X, 120 acres from R.A. Holland from Lubbock County for $3200.00. The plat, which can be found in Record Books at the court house, was dedicated in 1920. He had the town all laid out, streets named, sections dedicated to a school, the court house. All that was needed were the families to live there.

Josh sold some plots and families settled there, but he didn’t factor in that the town of Muleshoe intersected with the highway we now know as 214 and the railroad, which provided cattle loading facilities for the ranches and made Muleshoe a busier place than Progress. Muleshoe eventually became the county seat; the post office was moved there, and Progress didn’t progress as planned.

When Old Hurley still existed in the early days, Josh lived there and delivered mail three times a week on a bicycle, later adding a pony cart to carry heavy items.

At first a post office was at Lariat, but when it was moved to Muleshoe instead of Progress, he was so upset he turned against people in Muleshoe and called them thieves, and the people in Farwell were devils. And Josh still had his mail delivered somewhere in Lariat and walked there to pick it up.

And as time went by, he became even more resentful and eccentric as his little city continued to be overlooked. Progress schools were closed in 1937 and the students went to Muleshoe, which also took away his audience of school kids to tell stories to. One story he used to tell was that when he and his wife were coming from Kansas to Texas in a wagon, he stopped for her to open a gate and then drove off and left her there. Apparently he did have a wife, Mary E.C. Miller, and a son, but they never seem to be mentioned. I asked Pat and she said he was married and did have a son, but when Josh became so bitter over the feud with Muleshoe, his wife simply couldn’t live with the situation and she left him.

But when Josh moved here, he was not a recluse. He was out buying and selling land, selling the plots in Progress, visiting with people, telling outlandish stories and jokes to the kids. In time he even ran for county commissioner around 1917, but by then was considered a radical and was not elected. But as his anger ate away at him, his behavior became more erratic and strange. He never had a job, but instead would walk between towns, even into the town of Muleshoe that he was so angry with, and from the ditches would pick up trash, dumped items, soda pop bottles, scraps, anything he could sell or trade for something else. He heated his little hut using paper bags and kindling, had no electricity, no phone, and a dirt floor. Rats were said to share in this hovel. He would walk or accept a ride into town and then scavenge the trash bins behind the grocery stores and cafes for thrown-out spoiled, stale food. He would even at times ask people in Progress to fix him a meal. He grew a long beard and seem to wear the same dirty clothes all the time, which just added to the mystery of the man.

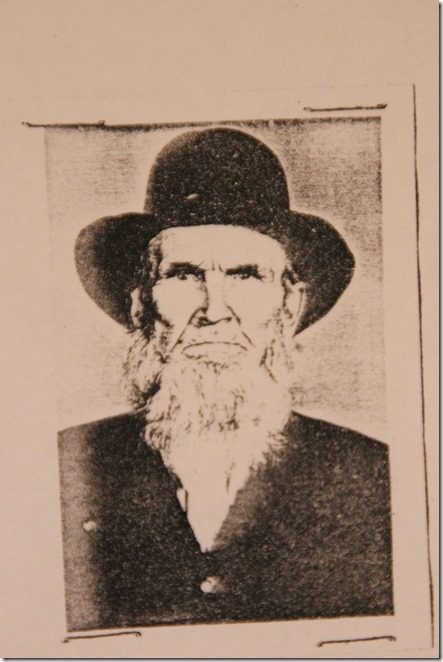

Photo taken from the Statement of Facts, Cause No. 387, State of Texas vs. Lester D. Stevens

It stands to reason that a man with this mindset would also not trust banks, and tales began to circulate that he hid his money, burying it in the dirt floor, stashing it under the bed or wherever else he could think of to hide it. Rumors then of course developed about how much money he had hidden over the years. Speculation went as high as ten thousand dollars or more, but no one knew for sure, which made it all the easier for the amount of hidden money to grow. He did hide his money, but the mystery remained as to how much and where it might be found.

Sadly, this rumor flourished and people all over the area began to hear tales about this old hermit who was rich and hid his money. An old man who lived alone with lots of money sounded like easy prey to Clifton Livesay from Amarillo who convinced fellow worker Lester Stevens that they should take advantage of the situation and rob the old man.

So they drove to Progress on a Saturday in August, 1951, either found Josh at his home or picked him up off the highway under the pretense of buying a lot, and drove off with him in their vehicle to a nearby cotton field. They were drinking soda pop and tried to get him to drink one they had laced with a barbiturate in the hopes the drug would make it easier to get him to talk. He turned it down because he said it hurt his stomach. So they beat him instead, first with one of the bottles and then with the butt of a hand gun. Being the stubborn, headstrong old man he was, he wouldn’t talk, so they beat him some more, took a coin purse or wallet of some type they found on him with keys in it, dumped him out in the cotton field, and went back to his shack to look for the loot.

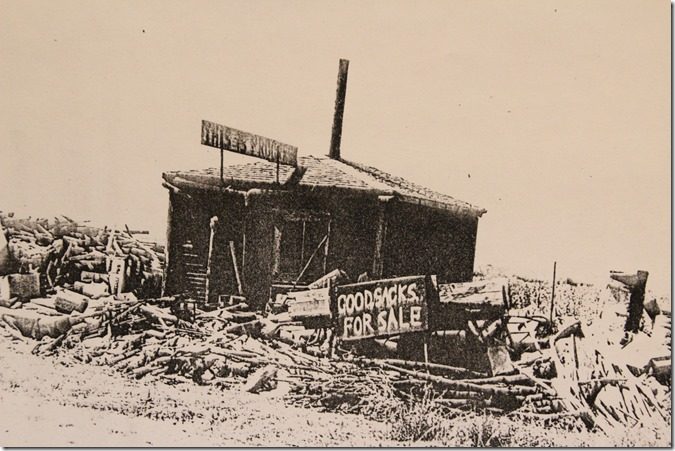

Photo taken from the Statement of Facts, Cause No. 387, State of Texas vs. Lester D. Stevens

They got into the old shack, dug around under the bed and found nothing. They hunted outside and found nothing.They then buried the coin purse by the railroad track and left for Amarillo where they talked just enough to make Stevens’ wife suspicious, left a trail for authorities to follow, and were eventually arrested.

When the men left Josh, he was still alive, and he tried to pull himself through the field in hopes of finding help. But his age, 85, and the severity of the beating kept that from happening, and he died out in the turn row of a cotton field owned by Harold Mardis, whose sons Clifford and Cecil Mardis found his sad, bloody body a few days later when they went to check on an irrigation well.

Dr. L.T. Green conducted the autopsy and said Josh died from a concussion, shock, and dehydration from exposure to the August sun. It was believed he was left in the field on Saturday but wasn’t found until the following Wednesday, so the sun was definitely a factor.

Besides the robbery being Livesay’s idea, Stevens claimed that it was Livesay who did the beating. Stevens also said they didn’t mean to kill Josh, leaving him alive with the hope that someone would find him and get him the medical attention he needed. But both men were found guilty and went to prison in 1952. According to an article in the Amarillo Globe-News from 1982, both men were to be tried together, but Livesay underwent surgery for appendicitis and Stevens was tried alone and sentenced to death in the electric chair. Then while Stevens was on death row at Huntsville, Livesay was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison; however, later Stevens’ sentence was commuted by Governor Allen Shivers to life as well because the state had failed to prove the murder was premeditated and both men were both equally guilty of the crime. Stevens later died in prison and Livesay was paroled after serving twelve years of his sentence.

What would cause a man to become so bitter and disillusioned that he would live in a falling down shack and survive on spoiled food and scraps from the garbage, eke out a living returning soda bottles for pennies and selling castoff junk he could gather? Some friends thought he had a small income from rent property in Progress, but to look at the piles of trash and junk hoarded around his little home, it would be easy to believe he thought this inventory would keep him solvent. In the trial transcript, R.L. Brooks talked about playing dominoes with the lonely old man and rubbing his head with liniment when his head hurt. Could it be Josh had a tumor or some other unsuspected medical condition that affected his behavior? Could it be he experienced some sort of hardship or trauma as a child that shaped his responses as an adult to the possibility of having no money or no place where he fit in? He wanted people to think of him as an intellectual, even finding and marking contradictory passages in his Bible, and he was said to have books on subjects ranging from phrenology to sex, but his erratic behavior only gave him the appearance of a scary, unpredictable, strange old man.

Progress still exists, but not in the way Josh envisioned it. His old shack, which stood on the south side of the highway and railroad, had to be torn down when Highway 84 was widened and made into a four-lane highway in the 60s. A few structures now stand further south in the general area where Josh lived, but there is no trace left of the old shack.

Not many people live in Progress now. The school is gone; the two grocery stores have long disappeared; a Baptist church building still stands, but I don’t know if it is still in use. The street names are no longer marked with their original names. Peach, Pear, and Apple, 1st Street, all were replaced with county road numbers after 9-11. Dirt roads still connect the blocks Josh marked off.

Texas Rangers, sheriffs, and other local authorities who conducted the murder investigation searched the old shack, inside and out, and also dug around in the ditches by the railroad tracks for the fabled money, but found precious little of it, and what they did find was so moldy, corroded and rusty it was virtually useless, unspendable for Josh or anyone else who might have come upon it. Most of it had to be sent to a government mint for the paper money to be pried apart and the coins cleaned to be at least partially counted. Reports varied, claiming no money at all was found, or that anywhere from $9,000 to $16,000 had been discovered buried in fruit jars in or near his shack, but the trial transcript said that only $190 was found by investigators. As to what the murderers took away from the robbery that day, one source quoted 13 cents while another said the robbers only found 37 cents.

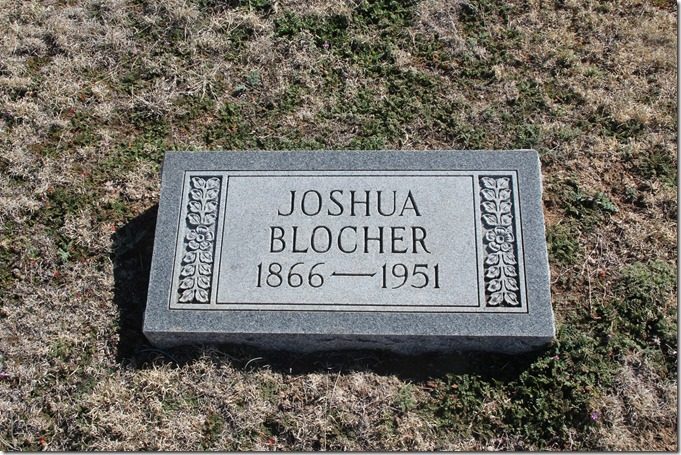

Josh was buried in the Bailey County Cemetery on August 20, 1951. The owner of the cemetery plot was not recorded, and no one else has been buried there. The grave, just like the man, will continue to be alone and silent, with secrets buried forever.

And the legend lives on that money is still buried out there somewhere, just waiting to be found.

Thanks to the many people who graciously shared memories with me and provided records and information: Pat Watson, Kenneth Henry, Nelda Hunt, John Gulley, David Wyer, Bill Liles, Corky Green, Patti Waggoner.

Bailey County History Book Committee; Tales and Trails of Bailey County, the first 70 years. Taylor Publishing Company, Dallas, 1988.

Statement of Facts, Cause No. 387 in District Court of Bailey County, Texas; The State of Texas vs. Lester D. Stevens, May 17, 1952; Clerk of the Court of Criminal Appeals, Austin, Texas.

Bailey County Court House Record Book and Bailey County Court House Index of Deeds

Tripp, Mary Kate. “Tripp: Amarillo author writing again,” Amarillo Globe-News, Web posted on Sunday, February 9, 2003, Amarillo, Texas

http://Bailey County Communities. cponboard.com/famhist/Bailey CtyComm.html

This was a good read! Enjoyed the story and learned something new about the surrounding area of Bailey County.

Love your blog Alice!!

Thanks, Martha!

Enjoyed the article. You captured the essence of Josh Blocher, as I remember him, quite well.

Glad you approve, Pat. Thanks for your help with the story.