In 1910 St. Mary’s Parish was founded in the tiny town of Umbarger, Texas.

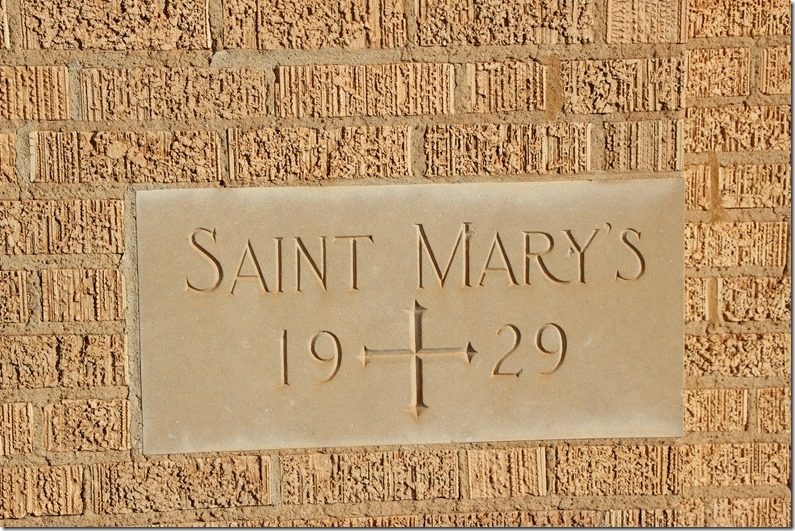

The first church building St. Mary’s had was a wooden structure on the south side of the railroad. In 1929 the present structure was built on the other side of the railroad in town and dedicated in 1930. It was a simple building with an all white interior. This was the beginning of the Depression years and funds to complete the church building and the rectory were hard to come by, but the work was finally finished, thanks to personal donations and community social events planned to raise money.

Fast-forward to 1943. World War II had created a need for prisoner of war camps in the United States. Texas, and the Panhandle area in particular, were considered good spots for a camp because the area was far away from the critical war industries on the East and West coasts and had a climate similar to where the prospective prisoners had been captured, which was Tunisia. A requirement coming out of the Geneva Accords’ rules of war was that the prisoners should be held in a climate similar to the one in which they were captured. Texans were agreeable to the idea of POW camps because the prisoners would be available to provide needed labor to fill the gap left by area men who became U.S. soldiers in the war. So it came to pass that Texas became the site of seventy-nine POW camps, the second-largest one being built in Deaf Smith and Castro Counties, a few miles from Hereford, Texas, off FM 1055 on County Road 507.

Hereford Military Reservation and Reception Center was the official name of the camp, and it was designated for Italian prisoners: 850 officers and an average of 2,200 enlisted men were housed in the camp. A few Germans were held there, but discord between the two groups created a prison riot, and when the Germans were moved to another location. Peace returned to the camp. Many of the Italian POWs were still loyal fascists, even after Mussolini was shot and killed, so the demeanor of the camps, including this one, depended on the American commander and how he ran things. At Hereford, things seemed to run smoothly, all things considered.

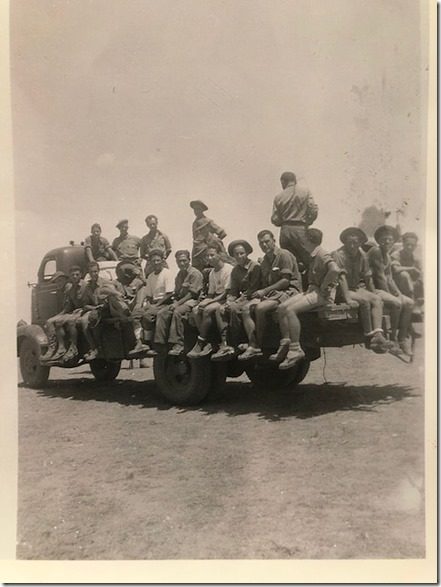

Farmers in the area, like E.K. Angeley from Muleshoe, would drive over with flatbed trucks or trailers to haul fifteen to twenty men to their farms to work in the fields, and his wife Alice would provide them with meals, which was part of the deal; if the men left the camp to work, they had to be fed by whomever was employing them. And feeding a group that size who ate military rations back at the camp was no mean feat! Based on my research, I think they were more than happy to be fed rather than paid money.

Photo courtesy of the Angeley family

The prisoners, however, did more than just manual labor. Umbarger is a short nineteen miles northeast of Hereford on State Highway 60. In August of 1945, Father John Krukkert, then the priest at St. Mary’s, visited the Hereford POW Art Show and was impressed with the work of the prisoners. At this time in Italy, artisans were said to be more in abundance than doctors and lawyers, so soldiers had talents. Father Krukkert inquired about having the prisoners paint the interior of the church building, and at first was turned down. The prisoners were still loyal to Mussolini and feared that doing this would label them as collaborators, which would cause problems upon their return to Italy. Eventually it was decided that if they accepted no money and were only paid for their efforts with meals, that would be appropriate, and they agreed.

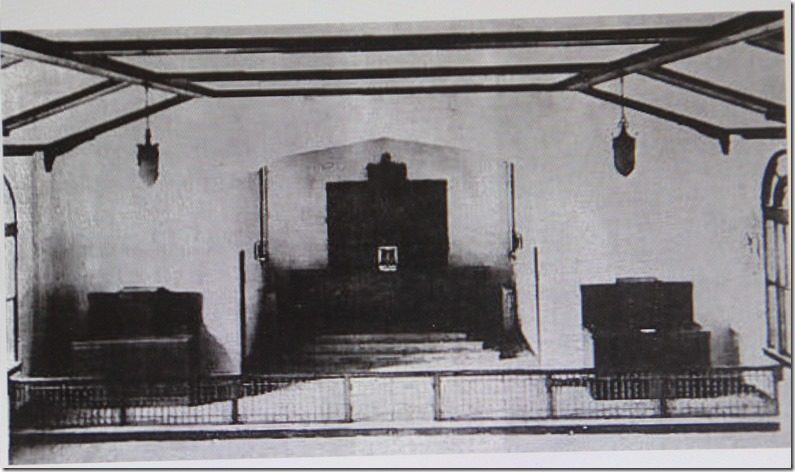

Work was begun on October 22, 1945. The interior of the church was nothing but white walls and frosted glass windows. The men set to work painting designs on the walls and murals of The Assumption, The Visitation, and The Annunciation. Two young girls from the parish serve as models for the angels and two local homesteads were envisioned in two of the murals. Christian symbols and medallions were painted all around the church. Prisoners Carlo Sanvito and Enrico Zorzi used wood provided by one of the parishioners to carve the Last Supper and decorative woodwork on the back altar.

Photo courtesy of St. Mary’s Church

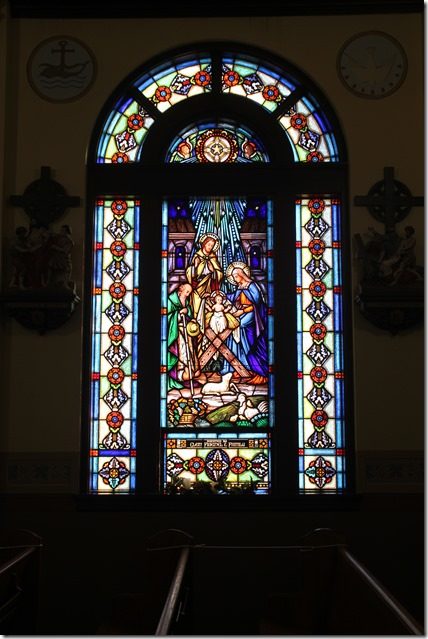

Stained glass windows that had been donated by families in the parish and ordered from a company in Wisconsin were delivered while the painting was being done. Because the windows had been made by artisans in the European style, no one in Umbarger had the proper tools or know-how to install them. These Italian artisans did, and had a local blacksmith create the needed tools to install the windows.

Before the men could finish their work, the war ended. Orders were received that they were to be shipped home to Italy. By then they had formed a trusting and caring relationship with the parishioners and the community, and being the artists that they were, finishing their work was important to them. They requested and were given three more days to finish before they had to leave. Finish they did, and the work was dedicated on December 8, 1945. And then they were gone.

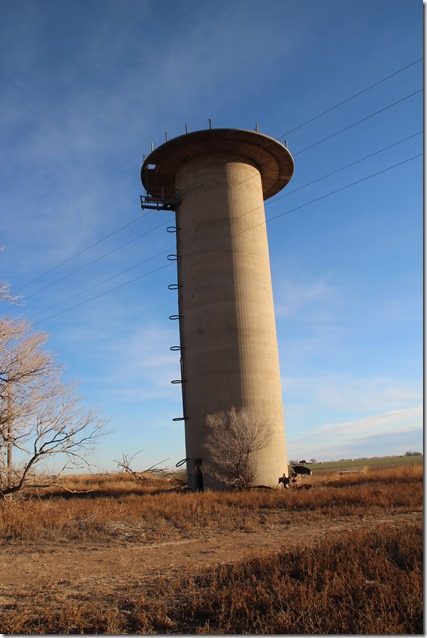

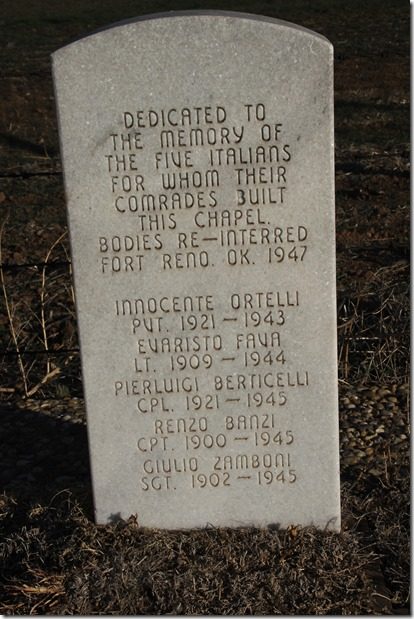

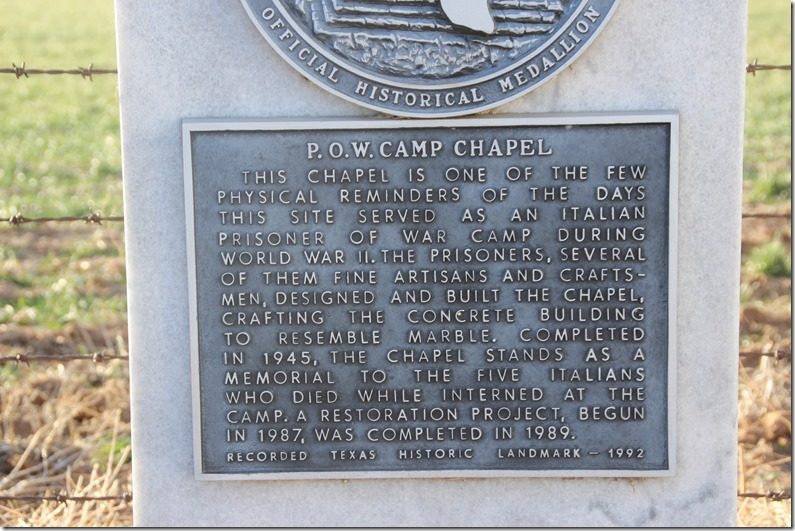

By February/March of 1946 the camp was officially closed. The deserted camp was declared surplus U.S. property. The structures were cleared off, for the most part, and the land sold to local farmers. All that remains is the abandoned water tower and a small chapel built by the prisoners as a memorial to the five prisoners who died while in the camp.

The chapel fell in disrepair over time, but was restored and rededicated in 1989. Some of the former POWs even returned for the event. The prisoners left a headstone naming the men for which they built the chapel and who had been buried there. Their bodies were later moved to Fort Reno, Oklahoma, and then returned to Italy sometime after the war. The Texas Historical Commission later added a marker.

The camp is gone, but the remaining structures can still be seen standing in fields of crops during the growing season and on empty, plowed land in the off season.

St. Mary’s is still going strong and looking pretty, thanks to the work of these artisans who lived in Texas, not by choice, but who contributed their skills by choice. A restoration of their artwork begun in 2012 and completed in 2018 keeps their work alive. The German Sausage Festival in November and the Fruehlingsfest (Spring Dance) in May are annual fundraisers that continue to support church projects and its parishioners.

A drive down FM 1055 will give you a view of the camp and chapel. A call to Debbie Batenhorst or Laurie Wegman will get you a tour of the church.

Not a bad afternoon road trip, I must say.

Thanks to Debbie Batenhorst, Pat Angeley, and Hellen Adrian for their help with this story.

For a tour of the church or information about the German Sausage Festival and the Fruehlingsfest held annually in Umbarger, contact Debbie Batenhorst at 806-499-3543 or Laurie Wegman at 806-499-3817.

https://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/WMF8YZ_Camp_Hereford_POW_Camp_Chapel_Hereford_TXhttps://texasplainstrail.com/plan-your-adventure/historic-sites-and-cities/sites/italian-pow-chapel-camp-hereford

https://authentictexan.com/camp-hereford-world-war-pows/

http://www.texasescapes.com/WorldWarII/POW-Camp-Chapel-Hereford-Texas.htm

https://www.findagrave.com/cemetery/2683956/hereford-italian-pow-camp-chapel-grounds

https://stmarysumbarger.com/history

http://www.texasescapes.com/Churches/Umbarger-Texas-St-Marys-Catholic-Church.htm

This such an interesting article. My wife and I could not stop reading and absorbing the wonderful photography of the art work. We look forward to each new posting.

Thank you so much, Ken! I am glad you enjoyed it. A trip to see the church in person is also worth the time.

Fantastic story. I knew about some of the prison camps in South Texas and some of the work they did.

The camp was a complete revelation to me. They did a lovely job on the church. Thanks for reading, Hal.

Great job, Alice. It’s good that there are physical reminders of this fascinating history.

It was a new history lesson for me.