Back during the 2011 drought, Keith and Brenna Burch were looking for a crop with low water needs. Vineyards were gaining attention in the Texas Hill Country, and vineyards take less water than cotton and corn. They did some investigating and also discovered that while the High Plains isn’t exactly blessed with a Mediterranean climate, it does have a lot going for it that matches the needs of grapevines better than what is found in, say, Fredericksburg: sandy clay loam instead of hills of granite; few insect pests compared to a wetter climate; low humidity due to much less rainfall; no fungus problems due to the drier climate; hot days and cool nights as compared to hot, humid days and warm nights; and enough ground water for irrigation when needed.

Grapes are a high-value crop that uses less water than other crops. Their other crops of cotton, corn, and milo were not abandoned, but the decision was made to give grape-growing a try, and by 2014, Burch Family Vineyards became a reality in Lazbuddie, Texas. They are now considered a medium-size vineyard with 30,000 vines of five varieties of wine grapes, 6,000 vines of each variety on twenty-five acres, and they ship grapes to wineries all over the state.

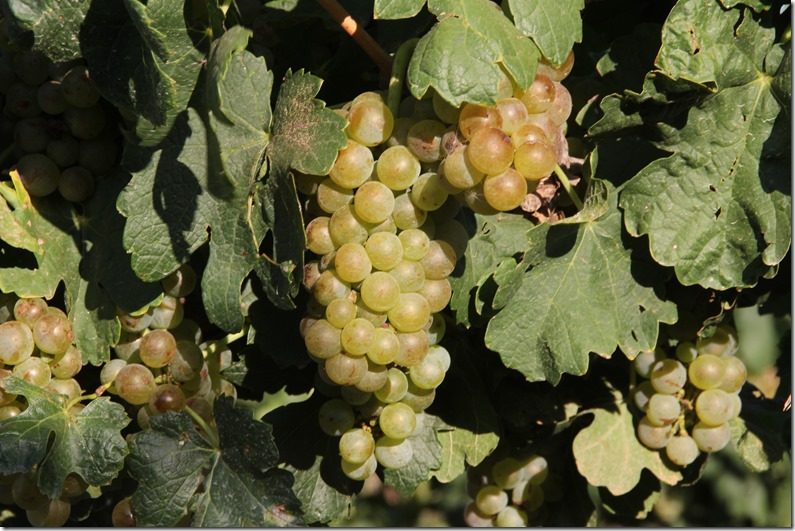

Burch Family Vineyard grows a Spanish grape, Rousanne, rousanne meaning rust-colored, which makes a white wine.

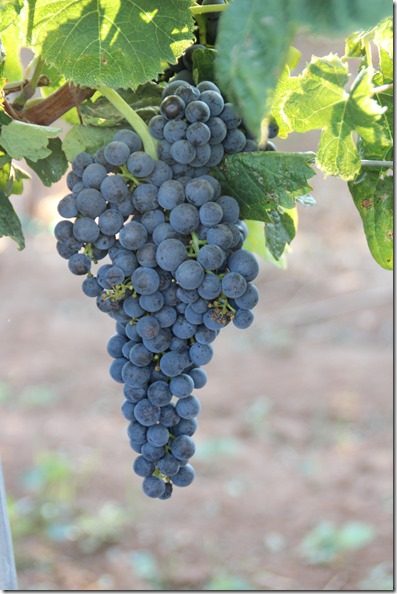

Tempranillo grapes are a Spanish red grape used to make red wine. I know, the grapes are purple, but the wine comes out red.

They also grow Rieslings, a green German grape which makes white wine, Pinot Noir, a purple grape for red wine, and Cabernet Sauvignon, a purple grape also for red wine. These vines were at the other end of the vineyard, and alas, I did not get down there to take pictures before they were harvested, but they look very much like these other varieties. I was told that red wines tend to have high alcohol content, whereas white wines have less. When you pick the grapes affects the amount of sugar in the grapes, which then affects the amount of alcohol that will ultimately be in the wine. And the sweetness or dryness of the wine is up to the winemaker and how the juice is processed.

Brenna explained to me that they are simply a vineyard; a winery is where the grapes are sent to become wine. Their grapes go all over the state. She also said that as the vineyard industry has grown in Texas, approximately eighty-five percent of all wine grapes are grown in the High Plains, which I thought was interesting because I suspect if you ask someone where the most grapes are grown, they would think of the Hill Country.

We looked at the vines and talked about watering and pruning grape vines, and Brenna showed me what healthy leaves should look like. She then showed me leaves that had been affected by the drift of the chemical dicamba, a herbicide used to control weeds in other row crops, which is the main problem they have keeping their grape vines healthy.

These are nice, healthy leaves.

These leaves have been damaged by drift from dicamba.

Deer, coyotes, and other small animals eat some of the grapes, but birds do the most damage. So at each end of the vineyard you will see what’s called an air dancer to scare the birds away. And in the middle of the vineyard we drove past a bird canon, which goes off about every ten minutes to scare the birds away. Apparently these two things are effective, because I didn’t see any birds flying around the vines.

Cover crops of cow peas, radishes, and rye grass have been planted between the rows to hold the dirt down and add nutrients and humus to the soil when they are plowed under later in the year.

Early fall is wine grape harvesting time, and I garnered an invitation to see how that harvesting is done. Table grapes are picked by hand; gathering wine grapes is a different ball game, so when Brenna said the time had come, I was ready to learn.

She said they would feed the crew about 6:30 and start the harvest at 7, but when I arrived at 6:30, mechanical difficulties were in full bloom and the harvest would start late. Mechanical difficulties are a fact of life for any farmer, but in this case it was a bit more complicated and frustrating because the harvesting machine, this one being a drag-type harvester because it is pulled by tractor, is made in France and all the directions on the cab’s computer were in French! And as you might have guessed, Keith is not fluent in French. Vineyard owners look to Europe for their harvesting machines, since vineyards and winemaking are historically and currently centered in Europe, and only one American implement company even makes a grape harvesting machine.

The self-propelled harvester, which I failed to get a picture of, had been having mechanical issues of its own, but it was put into service at the other end of the vineyard as night fell.

And nightfall is prime grape harvesting time because the temperature drops, which slows the fermenting process in the grapes, which starts during the harvest because the skins on the grapes are broken and fermentation of the sugars begins. So as the sun went down and the mechanical problems were fixed, the tractor pulled the harvester to a row of Tempranillo grapes. The tractor slides the harvester over to straddle the grape vines, lowers the beaters to grape level, and they begin to vibrate and shake the vines, knocking the clusters of grapes off and onto a conveyor that then deposits them in the tanks on top. When the tanks are full, they are dumped into bins provided by the wineries. Those bins are then taken to the winery in refrigerated trucks, or if it is cool enough, on open trailers, and the wine-making process begins.

As Keith drives the machine, Brenna walks behind for a row or two checking to see if too many grapes are dropped on the ground, calling for an adjustment in the timing and/or height of the beaters. When the tanks on top are full and are dumped into the travel bins, the process starts all over on the rest of the rows.

Keith’s dad, Kirby Burch, drove me in the four-wheeler down to the other end of the vineyard to see how things were going with the other harvester, and we found full bins of Pinot Noir grapes.

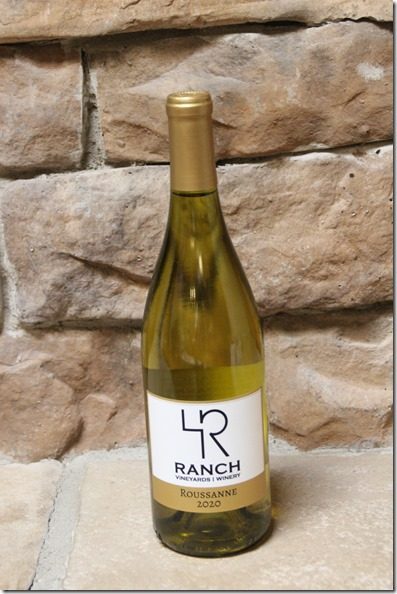

A refrigerated truck was waiting to take the full bins to the buyer of this batch of fruit, Wedding Oak Winery in Bend, Texas. Other Texas wineries they sell to regularly include Fiesta Winery in Lometa, 4-R Ranch Winery in Saint Jo, and Landon Winery in Greenville. Small towns are prime locations for wineries because land and facilities tend to be less expensive there. Wineries are usually just in the business of making the wine, not growing the grapes, just as a vineyard is in the business of growing the grapes, not making the wine. The exception would be an estate wine, when the bulk of the grapes are actually grown on site with the winery.

The Burch Vineyard grapes used to make this wine, for example, came from the 4-R Ranch Winery.

I left the harvest around 8:30 after I had seen all that it takes to get those grapes off the vine and on the truck. The harvest itself, however, was not over till 6:15 the next morning! Experienced hands like Joseph Lopez, Jose Beliz, and Carlos Perea make all-nighters like that successful because they know what they are doing and want the job done right. 2020 Lazbuddie graduate Avery Timms is also a valued part of the crew, and family and nearby friends help ferry children LIbby and Keller Burch to and from school or practice when harvest gets in the way. And nighttime harvest is a fact of life when the grapes are ready to come off the vine.

Photo courtesy of Brenna Burch

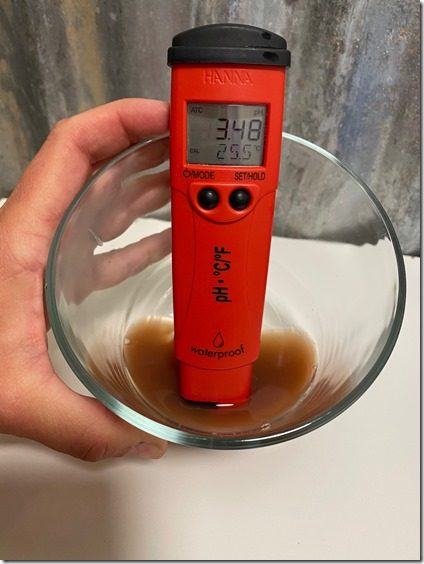

So how do you know when they are ready to come off the vine? You test the pH, that’s how. Brenna took me through the process, which she said starts when the grape seeds start to show streaks of brown. Before ripeness, the seeds will be lime green. The grapes will not be fully ripe until the seeds are completely brown, but the weather and the winemaker’s preferences sometimes cause them to harvest before that happens.

Photo courtesy of Brenna Burch

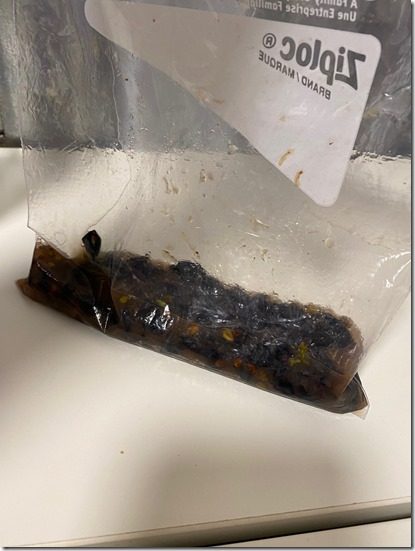

A berry sample, as it is referred to by viticulturalists, and Brenna is a certified viticulturalist-one who studies the cultivation and harvesting of grapes-consists of 100-150 berries randomly taken from various clusters of grapes within a block, which is all the rows of a particular variety. These berries are then put in a plastic bag and mashed up, releasing the juice. The contents of the bag are then strained, the juice collected, and the skins and seeds thrown away.

Photo courtesy of Brenna Burch

Photo courtesy of Brenna Burch

The pH of the juice is then tested with a pH meter to see if it is more acidic or alkaline. Acidity is an important factor in how the wine tastes, and a reading of 3.5 to 4 is most desirable.

Photo courtesy of Brenna Burch

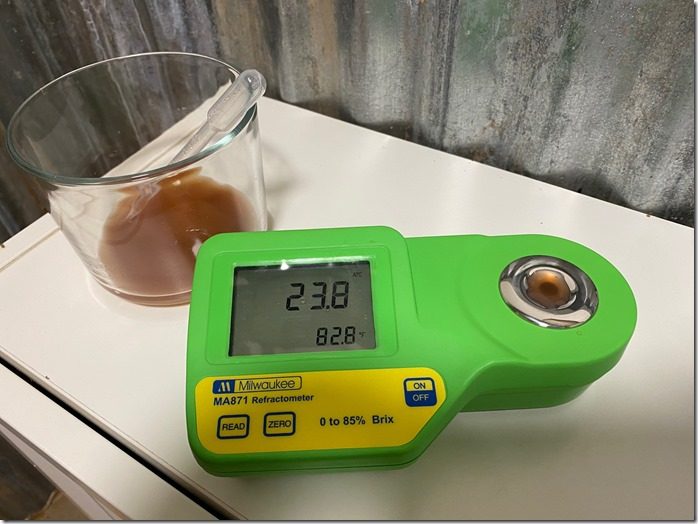

Then she tests the sugar content with a refractometer which sends a beam of light through the juice and measures the amount of refraction off of the sugar crystals. This is measured in degrees Brix with the desired reading being 14-20 for white grapes and 24-28 for red grapes.

Photo courtesy of Brenna Burch

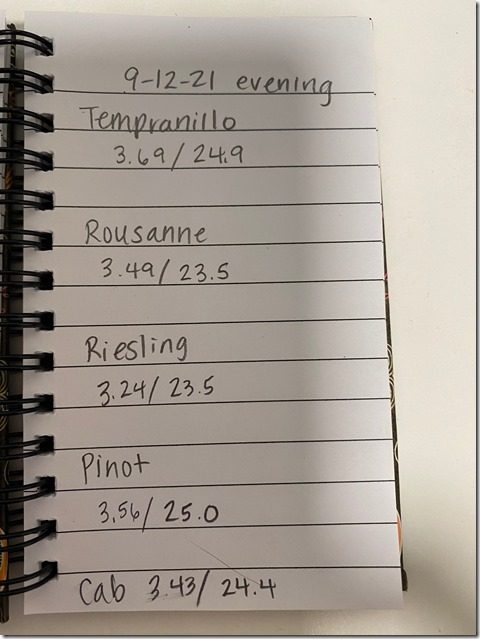

All of this information is recorded in a notebook and she then contacts the winemaker with the results, and together they decide when to harvest the grapes to meet the winemaker’s requirements.

Photo courtesy of Brenna Burch

The harvest began on September 9th and continued on three other nights; the last block of grapes will be gathered on September 23rd. Brenna estimates that with the final harvest, Burch Family Vineyards will have produced a little under 70 tons of fruit, perhaps their best year to date since the vines are now mature and producing well. The vines will now be heavily watered and fertilized at least once, maybe more if it is a dry winter, to help the vines store the carbohydrates necessary to insulate and protect the trunks through the cold winter months. Then in the spring the vines will be pruned and ready for another year of production.

Brenna grew up in Midland and graduated from Texas Tech in 2006 with bachelor’s degrees in chemical engineering and general business expecting a career in the oil business. Keith grew up in Lazbuddie, graduated from Texas Tech in 2001 with a bachelor’s degree in agronomy and a master’s degree focusing on crop science added later. When he came home in 2002, he became the fourth generation of the Burch family to farm the land in Lazbuddie. The two met in Lubbock, married in 2006, and she wound up a farmer’s wife far away from the pump jacks of Midland.

Brenna shared with me that she sees the farm as something spiritual that she truly loves. “There is something miraculous about the changing of the seasons-there is so much hope in the spring and so much joy in the harvest. I don’t know how anyone could farm and not see God every single day.”

She went on to say that while she is proud of the Burch multi-generational farm and its legacy, in a different way she is proud of the vineyard because it is, as she put it, truly ours. “We took a leap of faith together-just the two of us. With this leap came huge amounts of trust. I trust him to care for the vines in the way only a farmer knows how. He then trusts me to handle the crews, the winemakers, the marketing, and the timing of the various tasks throughout the year. To me this vineyard is a direct reflection of the relationship we share. A marriage that is rich in trust, love, and a whole lot of grace!”

What a nice way to end this story. I raise my glass to you both.

Thanks to Keith and Brenna Burch and Kirby Burch for their help with this story.

Great article, Alice. Never knew all that was involved.

Nor did I! Thanks for reading, Terry.

Nice story. Very proud of my niece.

She will be glad to know that. Thanks for reading.

Great article!

Great family!

Great Faith!

Love you guys! ❤️

Thanks for reading and commenting.

I’m very proud of my daughter and son in law. They’re not afraid of venturing out, innovating, and adapting to new challenges.

You have much to be proud of! Thanks for reading and commenting.